- Home

- George Barker

The Dead Seagull Page 2

The Dead Seagull Read online

Page 2

Then the door of the bedroom opened and Theresa came in noiselessly. “Are you awake?” she whispered. I opened my eyes. “I’ve brought someone to see you. He was the only person I could find that I thought you might like to see. He is a priest. He was walking along the shore. Shall I bring him in?”

“A priest? But I’m not going to die.”

“I could bring you flowers, or sweets, or grapes,” she said lightly. “Instead I bring you a friend, and what do you do?”

It is perfectly apparent to me that this state of quiet cannot continue for long. Too many emotions—fear, anticipation, love—exercise their stronger stresses upon us. All the while we live like two people who share an unmentionable secret, each suspecting the other of an incapacity to bear it much longer. Sometimes it seems that she hates the unborn child and hates me also; her virtue was her only garment and now she is naked to the worst winds of all the worlds. I think she sees her virginity with its face turned away weeping in every corner. The torn lips of the hymen hymenaeus need more than the lascivious hand of a lover to heal them.

There are so many necessary sins that nevertheless can never be forgiven. Who shall forgive the virgin mother for sacrificing her virginity and her self-love? Who shall forgive the infant for being? Let us utter a holy No to that greatest of all duties, the homicidality of love. Not all of those whom the destructive god visits can bring themselves to look upon the massacres that ensue. Bald tobacconist in Tooting High Street, I no less than the angel with the gold pen have seen that bed in the back room where three corpses lie under the sheets. The girl in a blue dress whose hope died when you last saw her on a Saturday evening, the mother who died when you pulled out the umbilical like a telephone wire, severing all communications, and the wife who had died under your infinitesimal infidelities. The desire of the whole is death where the pursuit of the whole is love.

* * * *

There is really so little to say of these months that preceded the summer when the child was born. I could almost wish that something had happened to us that, by no matter how twisted a rendering, could now be understood as a kind of foreboding. Or again, it may be that such omens were present but that, at the time, I had no eye for them. I saw a dog run over by an omnibus. I recall only that as it lay spread out like a torn oil painting on the road, I marvelled at the brilliant crimsons and the mauves and the blues of its shattered physiology. All it was, as it lay, could have been put together by a child with a paint box. What had the faithful eye and the affectionate tongue or the attendant allegiance or the courage to do with the colourful mess in the middle of the road? I know only one thing: it had obeyed its greatest master.

* * * *

No, destiny visited us in even more oblique disguises. On an April afternoon we walked in fields; Theresa, in a bright frock with a studded belt, and large, by this time, with child, but perfectly capable, went in happy spirits. “Let’s walk the whole afternoon,” she said; “we can take tea at a village on the way home.”

The lanes, with the flowering bushes fermenting along the banks, led us down from the hills. Sometimes a gold-tipped tree hung its head over like a lachrymal woman looking down into water. The weather, that afternoon, was perfect. It was quite warm enough for summer clothes. I held her hand and looked often at her; she would seem almost to smile but say nothing. She was full of her possessions; the day, the excursion, the embryo, the love, the husband, the vernal equinox of life, a pretty dress, a lipstick that made her mouth into a dragonfly alighting on her face. I thought that she had never been so beautiful as that afternoon; her pregnancy became her as it became those medieval women who so admired its lines that they wore gowns to give the belly a false size.

But before long she grew tired. She sat down on the bank by the side of the road and half laughing said: “I shall have to live here. I can’t move a foot.” I took her to the rear of the hedge, away from the road, and she rested in my arms. The white blossom was all about us. She gathered my hands to her breasts. It seemed to me that the whole world had gone procreant around my head. I could feel the reproduction of the species conducting itself in an orgy of imperious urgency inside every corpuscle of my blood. The pulse in my wrist leaped up like a line of lambs; the love had run loose throughout my vegetation, the banishment from paradise flashed between us, but we were beyond it. I took her, and, as I possessed her, out of the blossom, a yard or two at one side, I saw the most concupiscent face in the world, contracted with vicarious satisfaction, watching us as we lay.

* * * *

You are the first of my ghosts, you collision and collusion between the ovum and the sperm, you bullying embryo whom only the will of god wanted born, you stalked up and down the bed of our passion like a sentinel to see that we did not escape from you. I could watch myself staring at the big belly where my son was housed; I could examine the exact evolution of the jealousy that slowly soured into resentment and poisoned into positive hate. I saw my son pawing at me from the bulge and the bilge of his mother like a frog in an anthropologist’s jar, grinning with gratification, because it might be our Darwinian progenitor. I saw the contemplation of Theresa introvert itself, seeking, among the rocks of her own and her infant’s body, for the dove of individuality that must soon inhabit her child. Her curiosity, however, provides her with no answers. I am still the only victim for her virtues to revive. And, above everything else, the formidable knowledge that I have invented an instrument that can manufacture evil of its own volition: just as, of my own volition, I manufactured it.

O God, who did this, you, or I?

* * * *

Lucky dog, lying dead as paper on the road, what insoluble enigmas passed over your head! Whatever you did, the killing, the coupling, the chasing, the cringing, it was all the same—“this creature hath a purpose and its eye is bright with it”—you were the explorer of the experientially expedient. Whatever was, was right. In your world everything was necessarily best, down to the anatomical picasso your death stretched on macadam. Let the over-vulnerable biped continue to sweat and whine about its conditions. Every dog has its day.

* * * *

I had, one night in April, not many days after the event of the face in the hedge, a dream that took away some of the obscurity with which my feelings increasingly obfuscated themselves. In the day, everywhere I went I saw, with a kind of suppressed delectation, the figure of the child burning, it seemed, to ashes in the air. I saw this image in the broad daylight—it would appear, a tiny unnoticeable martyrdom, hanging in the branches of trees, or depicted in advertisements on the sides of buses; or in those happenings we witness in clouds. But the dream I experienced, this was an altogether different matter. It illuminated my jealousy of the child and of the mother; it equally illuminated the continual sense of my inadequacy and my unworthiness; it illuminated my positively albigensian attitude to the viciousness of human reproduction. I simply dreamed that I had become hermaphrodite.

* * * *

Yesterday Theresa received by the morning post a letter from a schoolgirl friend of hers with the improbable name of Marsden Forsden. Fairly automatically I assumed—I suppose from the association of the first syllable—that the schoolgirl friend was a young man—and then, without real reflection, I realised that it must be a girl. “Who is she? What does she want?”

Theresa gave me the letter. “She was to have been married on the same day that we were,” she said. “She would like to pay us a visit.”

“What happened? Why didn’t she get married?” I opened one of my own letters.

“She probably didn’t want to. She ran away.” I saw that, in spite of herself, Theresa wanted to speak about her friend. “It’s curious that you have never met her,” she said. “But she was one of those people one likes to keep away from one’s home, or one’s—what shall I call you?—one’s more valuable possessions. She has a gift of knocking things over with her intensity. She is almost the most beautiful person I have ever seen.”

I ligh

ted a cigarette and took up again the letter written in a large and careless script—it had something of the air of an edict in the capricious autocracy that condescended to none of the formal gestures of letterwriting. I saw between the lines the flamboyance of an actress perhaps a little too confident of her audience. “It’s an interesting hand,” I remarked, almost for the purpose of eliciting a contradiction. “It invites one to speculate.” And because I had nothing else to say: “Was she with you all the while at the Sacred Heart?”

“The Mother Superior expelled her. She isn’t a Roman Catholic. I forget what she was supposed to have done wrong. It wasn’t important. Her misfortune was always to have a little too much money.”

“What does she do with herself? I suspect she is an actress.”

“Her father sent her around the world with an aunt when she left the convent. I haven’t seen very much of her since then. I shouldn’t think she actually does anything. She used to have literary ambitions, but I imagine they’ve evaporated.”

“Why?”

“Oh, she was an eccentric creature. She’s probably an aeronaut now.”

I detected an inflexion of resentment in Theresa’s tone. “I get impatient with her,” she concluded, “because although the world may be her oyster, it’s mine too.” She began to clear away the breakfast dishes. “Shall we invite her to come? I think that you will find her entertaining. And I should like to see her again.”

* * * *

No matter how I endeavour to disguise it, I am increasingly conscious of what I can only think of as a distance supervening between us. For, as her concern the more intently turns inward towards the child, it turns, necessarily, its face away from me. I see her now as a pregnant mother rather than as a woman pregnant. And the knowledge that my love itself is responsible only renders the paradox the more unbearable. It is not, I repeat, that I am puzzled and frightened and resentful of our love being turned, by a germ in our genetics, to the irreparable personification of original sin. Her fulfilment in the child seems likely to be so perfect that everything else will be forgotten—it is for this simple reason that I cannot help suspecting that the woman exists in a lower category of spiritual consciousness. I wish to god I could be fobbed off from the omnipresence of evil by merely fulfilling my function as a father. But through the body of the suckling mother I know that biological obedience suffuses itself in an absolute benediction. With the sore dug plugging, the bub lugged out of an opening in the smock, the small man sucking, the grunting, the drooping udder, behold the mater amabalis, the virgin with a piglet, the pig with a saviour.

* * * *

That supremely placatory face, with its forehead like the masterpiece of a monumental stonemason, its lips spreading altruisms through which no rain can reach us, its eyes, half opened, enlightening all enigmas, and the altar above the upper lip dedicating this face and all human faces to the communicability of love: this is the face I see behind all faces. And always it wears a gaze of solicitude that seeks to dissolve the plaster masks through which we spy upon it.

I believe that under the plaster cast each one of us is a possible deity and a probable daemon. It is the probable daemon that commonly breaks out of our plaster. For the god will not emerge of his own deliberation—in order to expose him we must shatter ourselves upon him.

* * * *

Therefore women give birth because it might be a god.

* * * *

Now I get drunk every evening. The Goat and Compass, a little pub like a tea-cosy, where the easily consoled keep warm, provides me, also, with easy consolation. But it is a consolation shot through with livid ineffectualities like tiger traps or stage drops. I rehearse conversations, as I sit, in which I render myself incontestably right in desiring that the child should die. Also I get very sick.

In the half darkness as I go home to the cottage a derisive voice points its finger at me out of a cloud and jibbers: “You got born! You got born! You got born!” Not so much in disgust as in resignation I experience the aphrodisiac of the alcohol on my erotic system, and under a hedge, raging in despair, I have taken two million sinners out of my fallibility.

* * * *

Regal Theresa, can you forgive me, now, from wherever you are? My least forgivable infidelities were those with myself. The inhabitants of the heart, these are the inveterate enemies; and of these inhabitants, who except oneself is the principal? What on earth does one do at a crossroad except become two? When the veils are lifted from the truly religious man he will be seen kneeling in the masturbatory attitude of prayer. For he has intercepted the fiendish will of god with his hand in an immaculate contraception.

* * * *

Yesterday Marsden Forsden stepped down out of a Venetian ceiling into our hospitality. She is, certainly, a great beauty. Theresa was delighted. I left them together as soon as the three of us got home from the station. They cooed and chirruped and sniggered and smiled, quite undisguisedly elated at seeing each other again. Leaning their heads together over the small tea table, I thought, when I returned from a walk, how ravishing a picture they composed: the gold hair falling around the architectural face of the one who at that moment held her hand with seeming unconsciousness beneath her left breast, glittering and pink, winged cherubs in the air about her head; and the dark coiled mass of Theresa’s curls coming down over her shoulders like Monica’s modesty, failing to hide the big belly and the big breasts, shadows and muted instruments about her, the gracious leaning of her head forward and to one side over the tea table bringing the bright and the dark heads together in an intermingling of auras. I could have wished, they seemed so full of symbols, that at that moment there was no one else in the whole world: for it would still have been full.

“Come and take some tea,” Theresa said. “We were talking about you.”

“Don’t stop now. It’s plainly the subject he’s most entertained by.” Marsden, smiling, opened her eyes a little wider so that the remark masqueraded as flattery.

“My conversation can’t possibly compete with so much beauty,” I said shortly.

“More. And thicker. With a cherry on the top.” Marsden licked the back of a spoon rather like a big brindled cat licking its forepaw. She appeared perfectly at her ease; I had a disquieting feeling that I was the only person in the room not intimately familiar with the other two. Theresa, seeming to sense that I was slightly at a loss, said: “Marsden knows you very much better than you suspect. She’s been a fan of yours for months. She read your book.”

“It’s my misfortune,” I said. “I just can’t keep my mouth shut about myself. Sometimes it’s very embarrassing. What a tiresome turn the conversation has taken. Let’s talk about Marsden.”

Theresa looked with solicitude across the table. “What’s the matter?”

“I don’t know.” Marsden handed me a cigarette.

“You two milkmaids with your buckets full make me feel angry. I have the sensation that the schoolboys have when they see their superiors not going to school. I resent the fact,” I said with an amusement I could not conceal, “that women grow old quicker than men.”

“Grow up, you mean,” Marsden said.

“I do not mean grow up. Women never grow up. They remain children playing with dolls all their life long. Only the dolls become more and more expensive until finally they refuse to play with any but those that have cost them their virtue and their vanity.”

“Is he always like this?” Marsden asked Theresa.

“Yes, I am,” I said; “you’ll find me down at the pub. I wish you’d both come. I’ll be more sociable then. I got out of the wrong bed this morning.”

* * * *

“You must be nicer to Marsden,” Theresa said one afternoon when her friend was sleeping, “because if you aren’t she’ll fall in love with you.

“I should think she falls in love without any provocation. Say every Wednesday. I wonder whose mistress she is.”

“You mustn’t say things like that. You don’t

really dislike her. I’m not sure that you’re not simply envious of whoever she’s chosen to fall in love with.” She came and looked up at me with an expression of amusement that did not conceal a degree of real concern. “Are you?”

“I think she’s a very desirable residence,” I said, taking her hands. “But I have one of my own.”

* * * *

“I couldn’t sleep.” Marsden, trailing a long red gown, came in, yawning. “I hate animals,” she announced; “I feel so like them. Let’s have a brilliant conversation. Do I look beautiful?” She postured her dishevelled head, as she sat, up to us. Her gown, lightly tied at the waist, slipped down from her leg. She had swansdown slippers on her brightly pedicured feet.

“You look entrancing,” Theresa said. “All of you.”

“Oh dear” Marsden gathered her gown over her breasts. “Let’s go for a walk. Let’s go for a swim. Let’s go for a drink. Let’s go for a retreat. I’m going to go out and watch birds.” As she reached the doorway she turned. “But does the cut worm really forgive the plough?” she said in a querulous voice. “I decline to think so.”

“Hurry up,” Theresa called after her. “We’ll be out on the shore.”

* * * *

The sea, without a ripple disturbing the surface, spread out in sheets that glittered in different distances; at this point along the coast half a dozen toothy and saturnine rocks vaulted out of the shadows. The light, angling through clouds, invested everything with an eerie and livid artificiality. It was a landscape—a seascape—of prehistory. At any moment, out of that mud-flatted sea, the first monstrous amoeba might emerge, trailing the whole disastrous and grandiose history of biological life behind it. And I could see there, lying under the still water, the skull of the last of the species, festooned with seaweed—algae in the eyes—the miserable, ignominous necrophilia that will one day end it all. And, intercommunicatory between these two, the first and the last, I saw suspended, glittering, as it were, between the amoeba and the skull, the umbilical of the eternal maternal. Upon this cord, I heard the almighty announce in thunder, I shall hang the world. So that, like a skinned rabbit dangling in a gallows, each of us has, in his time, met his proper fate in this beginning: we have each been born with a rope around our necks. The mother of all living, lariat in hand, will never let us go.

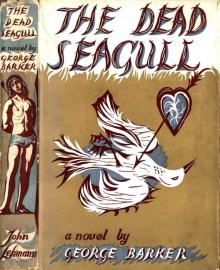

The Dead Seagull

The Dead Seagull