- Home

- George Barker

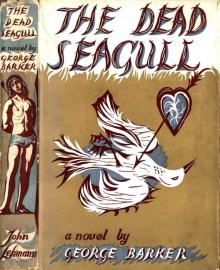

The Dead Seagull

The Dead Seagull Read online

THE DEAD SEAGULL

by

George Barker

London: John Lehmann

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1950 BY JOHN LEHMANN LTD

6 HENRIETTA STREET, LONDON W.C.2

Table Of Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

Dedicated

to

Michael and Didy Asquith

ONE

I WAS BORN IN THE MANSION OF THE VIRGIN in the year that preceded the declaration of the war that ended war. I write this in the year that ends the war that succeeded that war. I speak, therefore, as a person of whose life a third has been spent with violent death about it. This book has as its ulterior objective the effort to console myself and those I love—I mean you—for the insolubility of a problem about which Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote in the following terms: “As to other great questions, the question, what becomes of man after death, we do not see that a highly educated European, left to his unassisted reason, is more likely to be right than a Blackfoot Indian.”

* * * *

There is a story to tell, a story that has no place in history and no real claim upon the attention of the Fates. I have a story to relate which proves that Love, with no blood on its knife, does not sleep easily, if it sleeps at all, until every one of its devotees lies dead. The great destroyer. In every bed. In every single bed. In every double bed. No, it is nothing new. It has a more formidable virtue than novelty. It is inevitable. Its virtue is that of the divine volitional victimisation. I warn you that as you lie in your bed and feel the determination of your lover slipping its blade between your ribs, this is the real consummation. “Kill me, kill me,” you murmur. But it always surprises you when you die.

* * * *

Rising one morning, I perceived that everything had changed. I cannot speak clearly enough; the change in the nature and the face of things, when, that morning, I looked out of my sleep at them, eluded me then, and still just as narrowly eludes me. It comes down, at last, to this: I was afraid.

What does one fear when one awakes in the mornings? Is it the day, with its major temptations and minor renunciations, its afternoon misdemeanours, the sins that come up sighing out of the twilight, the suicide that smiles down at one from the midday sun, the death of a favourite dog at a quarter-past three, the resolution that will get itself born at an unpropitious conjunction of monsters, stars and houses? Or is it the quite conscious foreknowledge that, everyday, like stripping the calendar, we must cumulatively die?

They can so mercilessly and so incontestably out-manoeuvre one, the hours that weigh tons— daily, nightly, devastate the capitals of our faculties.

What war is it we cannot win? Is it the war that we won when we were born; the always precarious victory in between two annihilations; the defeat that, in the end, consoles us with wreaths of suitable flowers.

* * * *

I say that I awoke and perceived a change. Existence, removing the mask of the common-place from her face, looked in at the window and smiled. I heard the paradoxes at the heart of things hushing themselves out of hysteria into sleep. I went to the window and looked out. I saw Wilhelmina Stitch being torn into pieces by archangels.

* * * *

Hitherto, Augustine, I have believed in the virtues of love. Over all of the world I sensed its supremely proper benevolence, placing the candles of its illumination in all those rooms and at all those removes where, but for its presence, nothing but the shadows of appearances and disappearances would have depredated upon each other in irreligious irresponsibility.

Hitherto, I say, I have believed in love. I perceived that in the mechanics of the cosmological engines the function of impulse was provided by this love. From the internecine copulation of beasts to the image that reflects itself on the contemplative lake inside the skull of the visionary. This love, happening, as I saw it, between all kinds of things in all kinds of conditions, so that objects in one category could never consider themselves safe from the advance of objects in higher or lower categories—this variegated love validated everything. It moved the sun, the moon, and the other stars. And it was the evolution of this love, compelling all interdependent life to take place, that, seen in retrospect, was the will of God. And the peace that ensued from its fulfilment smiled on the face of the violated girl just as clearly as on the mouth of the intercessional prayer.

* * * *

One has to speak at some length about oneself. Why? Because everything begins, as it ends, at the egoistic heart. “Man,” I heard the shade of Disraeli interpolate, “is only truly great in his passions.” The passions of the egoistic heart have erected themselves marvellous memorials in places that the admirer can never visit, like the cairn that commemorates Captain Scott at the South Pole. Others, greater than this simple and vainglorious hero, have established their monuments in even remoter regions. Such as Antony who died on the Everest of the sensual, or Abelard who lived a long life in a cave of chastity that he could not abandon. Each of us, I suspect, has his own epitaph to earn, but the life upon which it will stand, this is our own responsibility. The sins that we feed with crumbs and cakes will follow us home; the virtues upon whose tails we failed to place salt will never attend us; the crime done in a hot bed will in turn engender a criminal.

* * * *

My father, a man of small means who lived in a southern county, had three possessions and he was incontinently fond of each. He loved his mother, his father, and himself. His affection for his two sons, eyeing the advance across a generation, hesitated, shied, and then turned inward upon himself. My brother and I would look back at him, wherever we were, and at all times, in the knowledge that his sympathies were not for us.

He had been a soldier. For several years after the war he continued to use his military prefix of Major. Normally loquacious, he spoke too much of war. And then, one day, he discovered two adolescent strangers in his house, one painting a picture of horses killing each other, and the second, the elder, myself, writing a thesis to disprove the existence of God. Not unkindly he remonstrated with us. Money was short, he explained; and expenses, after the war, exorbitant. If the times had been otherwise he would, he assured us, have been happy to have sent us together to a secondary school in the capital of the county. But, as things were … he left the sentence hanging about in the air and walked slowly from the room. I deduced that he was inviting his sons to get jobs. And the next night, quietly, as though it were an indelicate obligation of the body, he died in his sleep, leaving that unfinished sentence over our heads like an injunction from the hereafter.

* * * *

My brother, who, because he happened to be a couple of years younger than I, delegated me the decisions that we knew we shared, came, then, to a decision of his own. He decided that he was a painter. And that, as far as my brother is concerned, is that. I see no reason why I should say anything more about him; during the time that intervenes between then, when he decided he was a painter, and now, when I write this, he has simply gone on painting pictures of things that kill each other.

And at this point there is no one left in my story but me and crossed stars.

* * * *

Where was that house in which I first encountered love? What irresponsible collocation of improbabilities conspired to bring together at the same time and in the same place the victim in his yoke of roses, the goddess with her urgent appetites, and the altar of human sacrifice on which the heart breaks? That meeting of the improbabilities had occurred long, long before I knew it. I met her, in my youth, when she wore a gym slip and long black stockings, carried a pile of exercise books under her left arm, and, being three years older, had not really noticed the precocious boy who, years too soon, carried a sexua

l fox in his vitals. She was tall and dark, and her eyes had, even then, those depths in which, shadowed, great aspirations, dreams, like white whales, lay, scarcely stirring the surface, thousands of fathoms down. It is too simple. I spent my youth and my adolescence writing about her; we became engaged when I was seventeen; and two years later, on an afternoon in November, we were married.

* * * *

O nurturing tender Theresa, sweeter than a soft wind over a hurt hand, rise and accuse me. Turn in my wounds like a knife in a grave. Wherever pity is she has an indigenous place, and compassion, seeing her, comes up like a lamb for her administrations. What moved you, Aphrodite with the long legs, to tie yourself to the engine on which my character goes careering to its own destruction? Wherever I arrive I find my life in flames.

Those exquisitely melancholy afternoons of my adolescence, when I used to walk with the abstraction of a somnambulist through the damp avenues of Richmond Park, thinking that life would never happen to me, wondering why the banked fires of my anticipations, burning in my belly worse than raw alcohol, seemed not to show to strangers as I wandered in the gardens. And often it appeared to me, the frustration, in the disguise of an hallucination: looking between the trees that dripped with hanging mist I sometimes saw classical statues take on an instant of life, turning their naked beauty towards me; or I heard a voice speak out of a bush: “Everything will be answered if you will only not look around.” And I have stood waiting, not daring to look behind me, expecting a hand on my shoulder that would tender an apotheosis or an assignation—but there was only the gust of wind and the page of newspaper blowing breezily up and past me like a dirty interjection. Or a bicyclist flashed by, offering possibility until he reached me and decamping with it when he had passed. For I was suffering from a simple but devastating propensity: I was hoping to live.

* * * *

I cannot say that I knew anything at all about Theresa when we were married: I can only say that I knew nothing about anything.

* * * *

What can I reply, you admonitory ghosts, to placate your accusations? Why do you so daemonaically pursue me, I who have wished only to live with you and love you? Who are you, too importunate voices, responding with the condemnation “Guilty!” to all my appeals for help or consolation? Ghosts with your hearts held up like fatal evidence in your hands, you are the loved ones whom we have murdered. Just as, to them, we are among their unforgettable attendants.

* * * *

We honeymooned in a cottage by the sea; we were almost entirely happy. In the mornings I would walk along the rocky foreshore and then, returning, write for an hour or two. She would do those things about the cottage that our very simple life required should be done. They were not much; not exacting. She, too, would read a lot, or play with the kitten on a couch. But, earlier than our first day of marriage, we were never alone. Between us as we stood and kissed, the homunculus of origin, curled like a caterpillar, quickened. Wherever we were, we were eternally three.

* * * *

At night, downcast by the side of the bed, she would pray for our forgiveness. I could not understand. I could not bring myself to intercede for exculpation—my bed was made and I would not pray it unmade. I cannot forget how passionate her prayers were at that time—it was as though she knelt just within reach of the feet of the saints, and was silently begging them for their personal attention. Thinly clad in a transparent nightgown, she knelt with her hands crossed over her breasts and her head bent down on the bed. We had both been born and educated in the Roman Church—she wept sometimes, because I could not succeed in praying. Then she would rise from her knees, her eyes bright with restrained tears, and leaning over me, cover my face with her breasts. We were so deeply in love that old Adam slavered when we looked at each other.

* * * *

And some mornings, in the first winter of our marriage, we would lie late in bed, without breakfast, and talk about the past like a long-united couple. “You were a rather horrible creature,” I hear her whispering, “you were so conceited and so arrogant and so self-centred. And I was so much older than you. But you would never respect it.” And she would look up at me from the enormous depths of her eyes; eyes in which I knew that I should one day see, in the nine-month distance, my own face and nature finally fulfilled.

* * * *

We had a little money. Not much, but enough to buy food, a few books, a few small pleasures—the cinema, brief visits to London—and I was in expectation of receiving a grant of money from a literary society.

* * * *

The cottage in which we lived cost virtually nothing—it was remote and in an unfashionable part of the county. The sea dashed its spray on our southern windows and the gulls, on quiet days, strutted about on the whitewashed window sills. We could look out and watch ships crawl across the horizon, taking a whole afternoon for a voyage that, with our eyes, we could cover in an instant.

Or we would walk together over the hills by the sea. And as the gestation made its claim upon her body and upon both our minds, so our talking, as we walked, died away. Often we did not speak for an afternoon or an evening. We could observe on her body the measurable dimensions of sin. O that heavenly hour beside a river in Wiltshire, with the swifts in the clouds and the boys, far off, bathing minutely in the river, when, under the tree of knowledge, hissing with invincibility, the serpent uncoiled from my loins at the injunction of her love! The dominant ovum devours us or destroys itself.

* * * *

I think that we were like those children of whom one reads in German folk stories—harmless and hand in hand, with flowers in their hair, they wander lost through forests haunted by everlasting presences. The consciousness of natural sin went with us on our walks or stared at us, like an image we dare not look at on the wall, when we sat, seldom talking, by the fire in the evening. The noiseless and overwhelming engines of procreation laboured about us in the room, paralysing us; I had continually the emotions of a person who stands under a dam and watches the walls quake and crack. Looking across at Theresa, I sometimes seemed to see those fissures open in her face through which, at the proper time, the flood of retributory suffering would rush out. Taking her face in my hands I sought to restore it with tenderness or with a kiss. But I knew that I was holding the broken shell in my hands, from which, as I say, at the right season, the proud flesh must come out strutting into the world.

* * * *

“What shall we christen it? We ought to make up our minds.” Theresa looked across from the bed upon which she lay resting and put down the book that she could no longer read.

“I thought you had decided yourself.” I went and sat beside her on the bed. “I don’t know why—I thought you must have made a choice—it is a simple matter to decide. Shall we christen it with the name that we both know is right?”

She smiled a little sadly and said: “I refuse to call the baby ‘it’ any longer. From now on he is Sebastian.”

* * * *

“I saw our lives, two naked and childish forms, huddled together for warmth in a dark corner of the palace of human existence. We waited for an angel to cry to us, ‘Waifs, it is time for you to come home.’ Uncomprehending we saw about us the happily damned indulging in happiness and damnation. Monsters got born, lived, flourished, and died, and no one recognised that they were monsters. Over our heads great ecclesiastics and equally great statesmen forfeited the future to the expediential present. Athletes of unparalleled prowess demonstrated the pointlessness of progress. A comedian wrote: ‘They cut down elms to build asylums for people driven mad by the cutting down of elms.’ Categories jostled and jigsawed about our heads in a sort of seasick anarchy. Only two things remained constant: the anguish of being and the anaesthesia of the kiss.” I wrote this at that time.

* * * *

Then the spring arrived; it brought a sensation of relief and amelioration. The bright light, touching her face as she lay carelessly sleeping on a yellow pillow, seemed to invest her f

eatures with an external smile. Her dark hair leaped about in what appeared to be an orgy of immobility. I saw, not for the first time, that her beauty—the imitation of the image—brought upon itself the responsibility of sin. Such beauty imperiously demands its own destruction. Love, the double fury, engendering the exhaustion of itself, passes, at its climax, into death. Just as the spring engenders summer and then dies of its own excess into the autumn and the winter. The fulfilment of love is death, no matter how long the corpse goes on walking.

* * * *

I confess that in those early days of my marriage I was not unduly curious about her sensibilities; for there seemed to be none. Perhaps I should put it another way: I remember no occasions on which our natures conflicted. It may have been by reason of the simplicity of the life we lived: it gave, after all, few opportunities for differences of feelings or opinion. And, again, we had, as children, played together; as adolescents we had held hands in cinemas; we had, without ever deliberately seeking to know each other, nevertheless learned, in simply being together, that with the other each was happy. We had, as they say, things in common: what these things were it is easy to say: they were our lives.

* * * *

There was a week when I was ill—every so often my throat had a habit of turning septic—and I lay for days in bed dreaming of fizzy drinks I dare not swallow or of peremptory operations that would put an end to the discomfort. From the bed I could look out of the window and watch the sea’s procession—I remember a small trawler far out, that, in the windless day, carried above itself a decoration of smoke shaped like nothing so much as a cornucopia and suddenly I was lost to the whole world. It was on other stars that people sat down in restaurants, or played ping pong, or risked their wages on thorough-bred horses, or died, or overthrew governments. I was in a tower of septic poisoning. The sea and the ship might have been painted on the window—silent, not really changing.

The Dead Seagull

The Dead Seagull